Everyone with a serious interest in Egypt’s past and present should visit the El Wadi El Gedid museum. It features artwork and artefacts from the area and Egypt’s past.

EXPLORE. CONNECT. CREATE MEMORIES

Farafra

lies north-west of Dakhla in a fertile triangular depression about midway between Dakhla and Bahariya; to the west is the inhospitable Great Sand Sea. Once known as Ta-iht, or “Land of the Cow,” Farafra has been a part of the Wadi el-Gedid, or “New Valley,” since 1958. Hathor, the cow-headed goddess of fertility and motherhood, is said to have been the inspiration for this name. This tranquil oasis in Farafra will come to an end at the greatest depression in the Libyan Desert, which is around 200 km in length and 90 km in width (at Qasr el-Farafra).

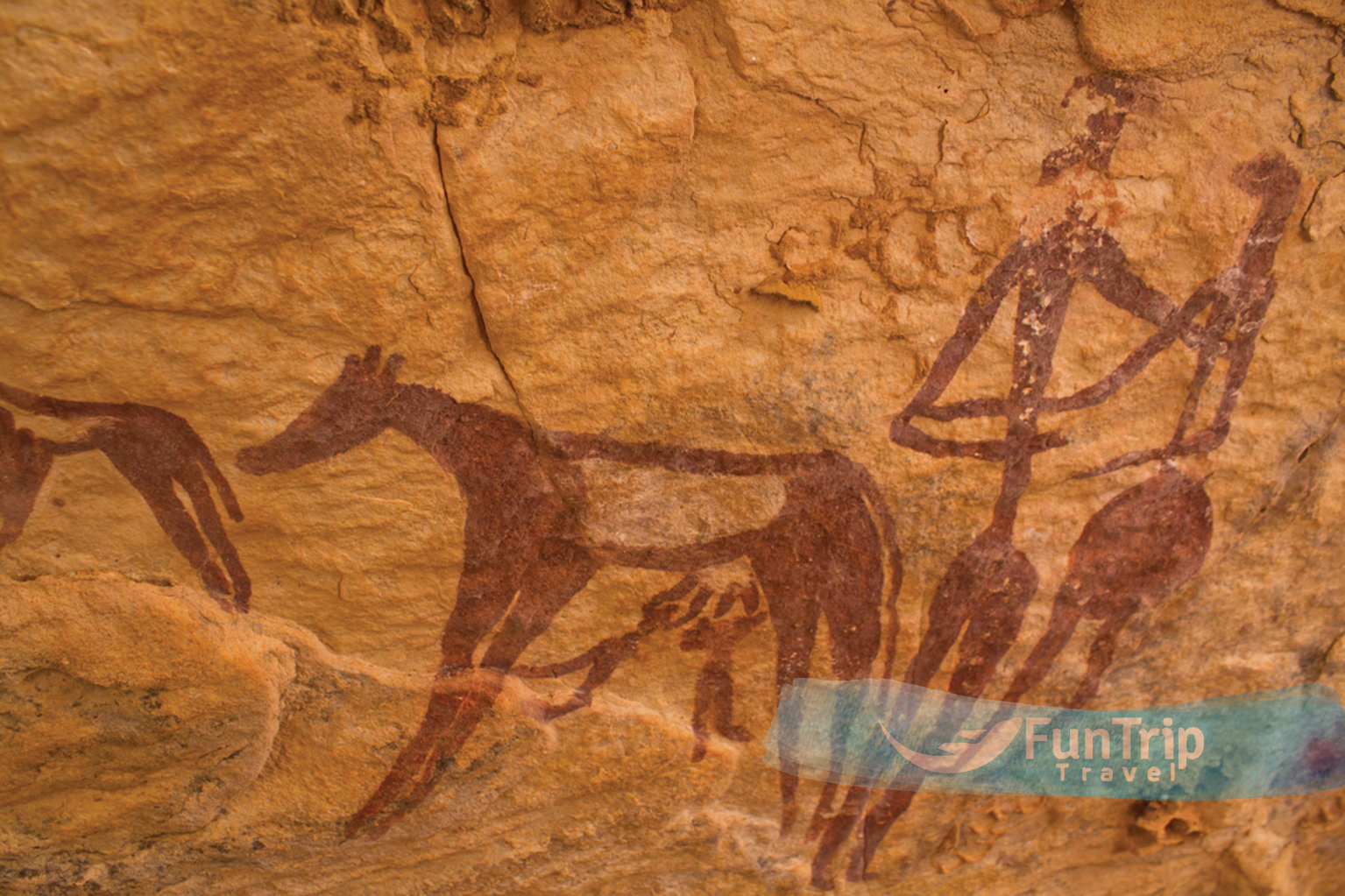

Gara Cave

The Egyptian Gara Cave was found by Gerhard Rolfes. It was used as a dwelling by our distant ancestors before the rise of civilisation. Surprised, he entered a peculiar gate in the heart of the plateau that had formerly served as the entrance to one of the subterranean cinemas dedicated to horror films. He claimed to have spotted hundreds of human inscriptions, indicating that some of the first people in the region had lived in this cave. Between Bahariya Oasis and Assiut in the Western Desert is a network of caverns known as the Gara Cave that are estimated to be about 20 thousand years old. Stalactites and stalagmites, a geological formation, fill the cave with cave paintings depicting prehistoric people engaged in hunting and other ritualised activities. Human paintings, cows, hunting equipment, arrowheads, spears, and stone daggers show that the cave region was not a lifeless desert but rather supported a thriving human community with all the amenities of modern civilization.

Qasr Al Labakha

Is a micro-oasis located 40 km north of Al Kharga in a desert landscape of desolation. The ruins of a four-story Roman fortress, two temples, and a vast necropolis where more than 500 mummies have been discovered are scattered among sandy swells and rocky shelves (you can still see human remains in the tombs).

Necropolis of Al Bagawat

It’s in Dakhala, This necropolis is one of the oldest and best-preserved Christian cemeteries in the world, despite its very meagre appearance from afar. Located approximately 1 kilometre north of the Temple of Hibis, it was constructed on the site of an ancient Egyptian necropolis and seems to include 263 mud-brick chapel tombs, the most of which date back to the 4th through the 6th century AD. The interiors and exteriors of several of these buildings are painted with vibrant murals depicting scenes from the Bible. Via the Greek graffiti on the squinches of the domes at the Chapel of Peace, images of the Apostles may be made out. The Old Testament tale of Moses bringing the children of Israel out of Egypt may be observed via graffiti from the 9th century in one of the oldest tombs, the Chapel of the Exodus. Chapel of the Grapes (Anaeed Al Ainab) gets its name from the depictions of grapevines that adorn its walls, and is part of a larger family tomb (No. 25) depicting Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac.

The Pharaohs Relics

Furthermore, the museum has an assortment of artefacts from antiquity that are difficult to come by elsewhere. Objects from the pre-dynastic period, such as prehistoric tools and vessels (including the uncommon red-colored variation from the ancient kingdom), are on exhibit. The museum also has paintings illustrating ancient life in the oasis as well as portraits from local temples including the Hibis, Ndura, and Ghweita.

Greek and Roman Influences

The Roman conquerors were particularly interested in El Wadi El Gedid because of its fortified location along the Nile and frequently had garrisons there. As a result, the El Wadi El Gadid museum contains many objects from this era.

The museum houses jewellery and other ornaments made of precious stones during the Greco-Roman period, as well as masks and coffins. There are also numerous carved images, such as that of Amun, the dominant Egyptian deity at the time.

Islamic and Coptic artefacts

Both Muslims and Coptic Christians have lived in El Wadi El Gedid at some point. Coptic Christians fled to the region to avoid persecution by Roman invaders at the start of the Christian era in Egypt. During Egypt’s Islamic occupation, Muslims focused on the El Wadi El Gedid region and the South in general. As a result, the El Wadi El Gedid region is rich in historical objects representing both religions.

Coptic Christians left sacred items such as crosses (wooden, bronze, and copper types), colourful portraits of various saints, Jesus Christ himself, and his mother, Virgin Mary. There were also a number of obscure Coptic manuscripts discovered in the area.

Muslims, for their part, left behind one-of-a-kind lamps that were once hung in mosques. There were also inscriptions of Quranic verses on wood and paper, decorated pots and other vessels, and various weapons used at the time.

Rock Carvings

Prehistoric petroglyphs of camels, giraffes, and tribal symbols are carved into the strange rock formations 45 km towards Al Kharga, where two important caravan routes once met. The site has recently suffered from the attention of less-than-scrupulous visitors, who have all but destroyed the majority of these strange images with their own graffiti.

Temple of An Nadura

Located on a hill to the right of the main road heading north from Al Kharga town, has strategic panorama views of the area and was once used as a fortified lookout. It was constructed to protect the oasis during the reign of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius (AD 138-61). The breathtaking views here are ideal for admiring the sunset.

Ain Umm Al Dabadib

This impressive fort is located about 20 km west of Qasr Al Labakha on a ridge that rises majestically from the desert plains. It has one of the most intricate underground aqueduct systems built by the Romans in this area. Trips here are considered serious desert excursions.

Qasr Al Ghueita

The massive outer walls of the garrison enclose a 25th-dynasty sandstone temple dedicated to the Theban triad Amun, Mut, and Khons. In later centuries, the fortress served as a village’s perimeter, with some houses still standing along the outer wall. A series of reliefs in the hypostyle hall depict Hapy, the pot-bellied Nile god, holding symbols of Upper Egypt’s nomes (provinces).

Despite the arid dusty landscape, this area, about 18 km south of Al Kharga, was once the centre of a fertile agricultural community renowned for its grapes and winemaking – the name means ‘Fortress of the Small Garden’. Settlement here dates back to the Middle Kingdom period, when it was known as Perousekh. Today, two strong forts from the later Roman period stand guard over the plains, most likely as garrison buildings for troops. An asphalted road leads 2 km from the main road to Baris to this imposing mud-brick fortress.

Qasr Ad Dush

About 13 km southeast of Baris, is an imposing Roman temple fortress built around AD 177 on the site of the ancient town of Kysis. A sandstone temple dedicated to Isis and Serapis was built next to the fortress in the first century. The gold decorations that once covered parts of the temple and earned it fame have long since vanished, but some decoration remains on the inner stone walls. Dush was a border town strategically located at the crossroads of five desert tracks and one of Egypt’s southern gateways. It could also have been used to guard the Darb Al Dush, an east-west path leading to the Nile Valley temples of Esna and Edfu.

As a result, it was well-built and heavily fortified, with four or five additional storeys hidden underground.

Deir Al Haggar

One of Dakhla’s most complete Roman monuments is this restored sandstone temple. It was dedicated to the Theban triad of Amun, Mut, and Khons, as well as Horus (who is depicted with a falcon’s head), and was constructed between the reigns of Nero (AD 54-68) and Domitian (AD 58-68). (AD 81–96). Some relief panels have been well preserved, but the majority are covered in bird poop. The temple is 7 km west of Al Qasr and 5 km from the turn-off.

Al Kharga Museum of Antiquities

This two-story museum, designed to resemble the architecture of the nearby Necropolis of Al Bagawat, is an old-school dusty trove of archaeological finds from the Al Kharga and Dakhla oases. The collection is small but interesting, with artefacts dating from prehistoric times to the Ottoman era, including tools, jewellery, textiles, and other objects that depict the region’s cultural history.

The Gilf Kebir

Is a stunning sandstone plateau 150 km north of Gebel Uweinat that rises 300 metres above the desert floor. The setting is as remote as it gets, with a rugged beauty that once drew the most ardent desert lovers; on the northern side, the plateau disappears into the sands of the Great Sand Sea.

There are some impressive rock carvings and paintings here. The stunning depictions of people swimming, known as the Cave of Swimmers, and abundant wildlife, including giraffes and hippopotamuses, are thought to be around 10,000 years old. The swimming scenes were an accurate representation of their surroundings prior to the climate change.

The Great Sand Sea

One of the world’s largest dune fields, straddles Egypt and Libya, stretching more than 800 km from its northern edge near the Mediterranean coast south to Gilf Kebir. It has some of the world’s largest recorded dunes, including one that is 140 km long, and covers a massive 72,000 km2 . Foreigners were not permitted at the time of writing.

Crescent, seif (sword), and barchan dunes abound here, challenging desert travellers and explorers for hundreds of years. The Persian king Cambyses is said to have lost an army here, and the British Long Range Desert Group spent months trying to find a way through the impenetrable sands to launch surprise attacks on the German army during WWII. Aerial surveys and expeditions have aided in the mapping of this vast area, but it remains one of the world’s least explored.

Gebel Uweinat

The mountain (Gebel Uweinat) is located on the border of Egypt, Sudan, and Libya. At 1934m, as its Arabic name implies, there are eight small springs within the mountain, despite its location in the most inhospitable part of the Western Desert. Ahmed Hassanein discovered the oasis again in 1923.

Thousands of petroglyphs on sandstone rocks, including depictions of humans that resemble modern Nilotic peoples, as well as lions, giraffes