Esna is a quite a big size town located about 55 kilometres south of Luxor (35 miles) south of Luxor. It is home to the magnificent Temple of Khunum, a Greco-Roman structure built to represent a much older monument built by Tuthmosis III during the reign of Egypt’s 18th dynasty. Most visitors come to Esna on the Nile’s west bank for the Temple of Khnum, but the bustling town itself is charming. Several examples of 19th-century provincial architecture with elaborate mashrabiyya can be found (wooden lattice screens). Immediately north of the temple is the Wekalat al-Gedawi, a beautiful but run-down Ottoman caravanserai that was once Esna’s commercial centre. Merchants from Sudan, Somalia, and Central Africa stayed on the second floor, and a market was held in the courtyard on a regular basis, selling Berber baskets, Arab glue, ostrich feathers, and elephant tusks. Opposite the temple is the Emari minaret from the Fatimid period, one of Egypt’s oldest, which survived the demolition of the mosque in 1960. In the (Al-Qisariya, 19th Century local market) south of the temple, an old oil presses lettuce seed into oil, a powerful aphrodisiac since ancient times. Until the early twentieth century, Esna was an important stop on the camel caravan route between Sudan and Cairo, as well as between the Western Desert Oases and the Nile Valley. It is also well-known for the two Esna locks on the Nile, where cruise ships must queue to pass.

EXPLORE. CONNECT. CREATE MEMORIES

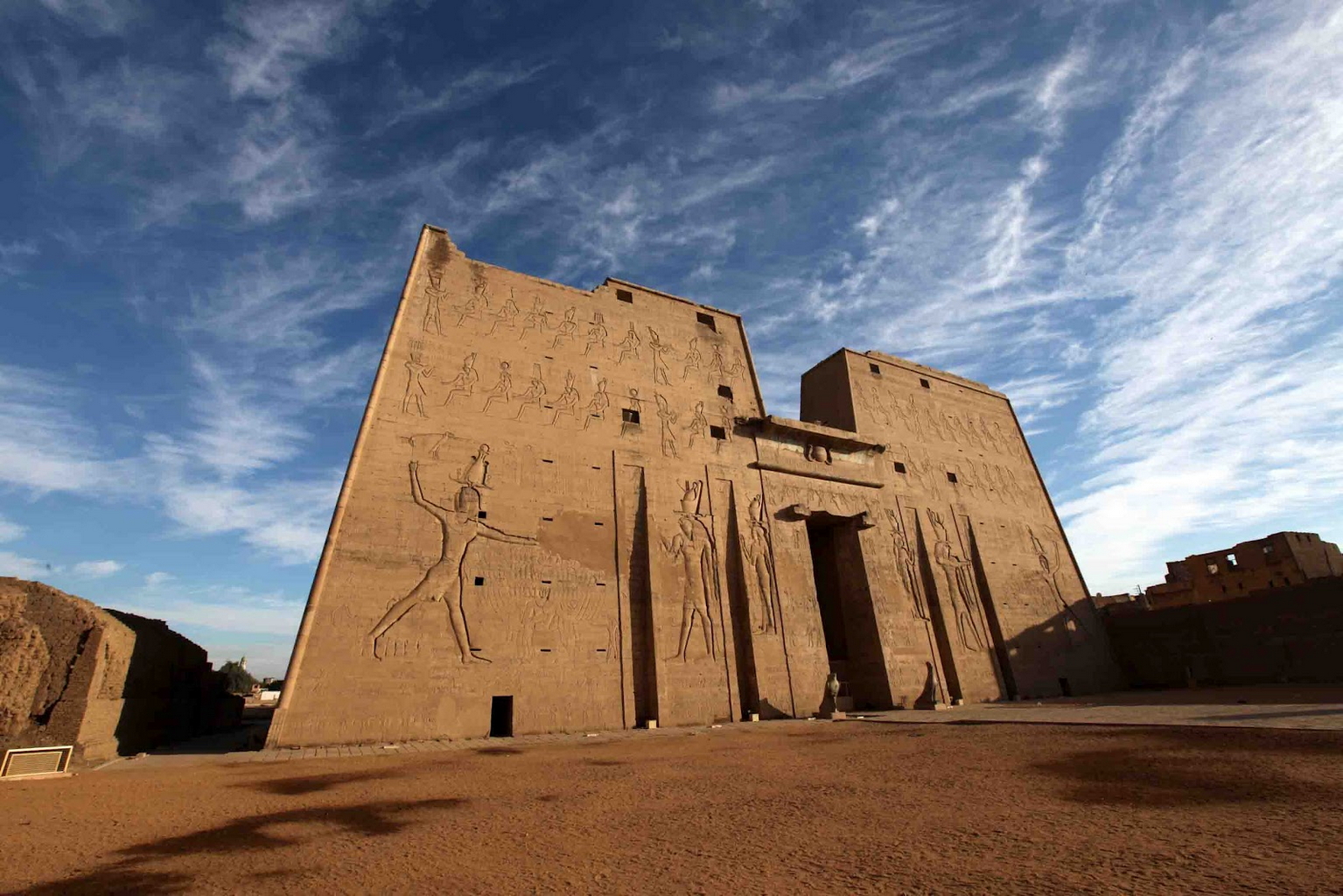

The Town Of Edfu

Today, it is an important centre for sugar production and pottery-making on the Nile’s west bank, 56 kilometres south of Esna and 105 kilometres north of Aswan. The modern town was named after the ancient Egyptian Djeba. The site of Edfu Tell was known as Wetjeset-hor the greeks called it Apollinopolis Magna, where, according to the ancient mythology the god Horus was worshipped and the battle between Horus and his traditional enemy Seth took place in ancient mythology. The main attraction in Edfu is the Ptolemaic Temple of Horus of Behdet, which is located on the outskirts of town. Edfu temple was visited by many early travellers despite being heavily covered by desert sand and human settlement debris. The sand has helped to preserve the building, which was discovered to be almost completely intact when Auguste Mariette first cleared and excavated it in the 1860s.Construction began here in the 3rd century BC, in the Ptolemaic era when Egypt was ruled by the Ptolemy Dynasty’s pharaohs. It is Egypt’s best-preserved temples, making it a major Nile side tourist attraction in Upper Egypt. Edfu’s temple is one of the most impressive feats of construction completed during the Ptolemaic era and is one of the best places to visit to experience Egypt’s temple builders’ audacious ambition. The looming sandstone walls of the temple are covered in massive hieroglyphics and dazzling friezes that mimic the patriotic decorations of earlier pharaohs. Within its vast chambers, strolling under colossal gateways and wandering ant-like through corridors that appear to have been designed for giants, you get a sense of Egypt’s rulers’ all-encompassing power. The temple is featured with its impressive pylon which is 36 meters high. There are two remarkable granite statues of Horus standing at the pylon at the entrance of the temple. The second, smaller pillared hall leads to the temple’s roof, which has spectacular views of the Nile. The staircase leading to the roof is decorated with incredible scenes of New Year celebrations, a ritual practiced in many temples throughout Egypt.

Kom Ombo

The most famous section of the Nile is the section running north from Aswan to Luxor, with its scattering of pharaonic temples along the palm-studded river banks. Kom Ombo is an industrial town 45 kilometres north of Aswan that was strategically placed as a garrison town on an important trading route between Edfu and Aswan.

The Holy Temple

The main attraction these days, however, is the unique riverside temple to Horus the Elder (Haroeris) and Sobek, which stands gloriously on a promontory overlooking the Nile about 4km from the town centre. Kom Ombo was once known as Ta-Sebek (Land of Sobek), after the region’s crocodile god. Under the rule of the Ptolomies, the city was called Ombos, which derived from yhr old Egyptian name Nebit, meaning gold, it became the capital of the first Upper Egyptian nome during the reign of Ptolemy VI Philometor. Kom Ombo served as an important military base as well as a trading hub between Egypt and Nubia. It was a market for African elephants brought from Ethiopia, which the Ptolemies required to fight the Indian elephants of their long-term rivals, the Seleucids, who ruled the majority of Alexander’s former empire to the east of Egypt. The Ptolemaic temple and ancient town site are located on a promontory on the Nile’s east bank, a few kilometres from the modern town.

The Construction

Ptolemy VI Philometor (180-145 BCE) began construction on the temple, but blocks of stone dating from the 18th Dynasty have been discovered at the site, indicating that some form of temple existed there prior to the current temple’s construction. Although Ptolemy VI started the temple, it was greatly expanded by the following Pharaohs, most notably Ptolemy XII Auletes (112 – 51 BCE) and Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator (61 – 47 BCE). The design and layout combine the two temples, with each temple located on either side, each with its own gateways and chapels. The entire complex was surrounded by a mud brick wall built sometime after 30 BCE by the Roman Emperor Augustus (63 BCE – 14 AD), though this has now mostly vanished. As one approaches the temple from the Nile, one passes the Ptolemy VII Birth House, which once abutted the pylon. The Birth House originally measured 18 by 23 metres and 9 metres high, but only half of that remains, including four Hathor columns.

Gebel Silsila

Is the name given to a rocky gorge between Kom Ombo and Edfu where the Nile River narrows and high sandstone cliffs descend to the water’s edge. In ancient times, there was probably a series of dangerous rapids here that naturally formed a border between the Elephantine (Aswan) and Edfu regions. The river here was known as Khnnui, which means “place of rowing” in Pharaonic times. On the West Bank, there is a tall column of rock known as ‘The Capstan,’ named after a local legend that claims a chain (Silsila in Arabic) once ran from the East to the West Banks.According to Arthur Weigall’s ‘Antiquities of Egypt,’ the name Silsileh is a Roman corruption of the original Egyptian name for the town, Khol-Khol, which means a barrier or frontier. It’s not surprising that by Dynasty XVIII, travellers had developed the practise of carving small shrines into the cliffs here, dedicating them to various Nile gods and the river itself.

Tuthmose I, Hatshepsut, and Tuthmose III cut smaller shrines before Horemheb built his rock-cut temple here, and many of the Dynasty XIX or later kings left their mark in some way. Gebel Silsila became an important cult centre, and each year at the start of the inundation season, offerings and sacrifices were made to the gods associated with the Nile to ensure the country’s well-being for the coming year. During Dynasty XVIII, massive quarries on both banks of the Nile produced the sandstone needed for the prolific construction of monuments. At first in small quantities, the stone was more extensively quarried to build great monuments such as the colonnade of Amenhotep III at Luxor, the Karnak Temple of Amenhotep IV, Ramesseum, and Medinet Habu, to name a few. By Ptolemaic times, most Upper Egyptian temples had monuments made of Gebel Silsila sandstone. Because of the site’s sanctity, the sandstone was thought to have extra holiness.

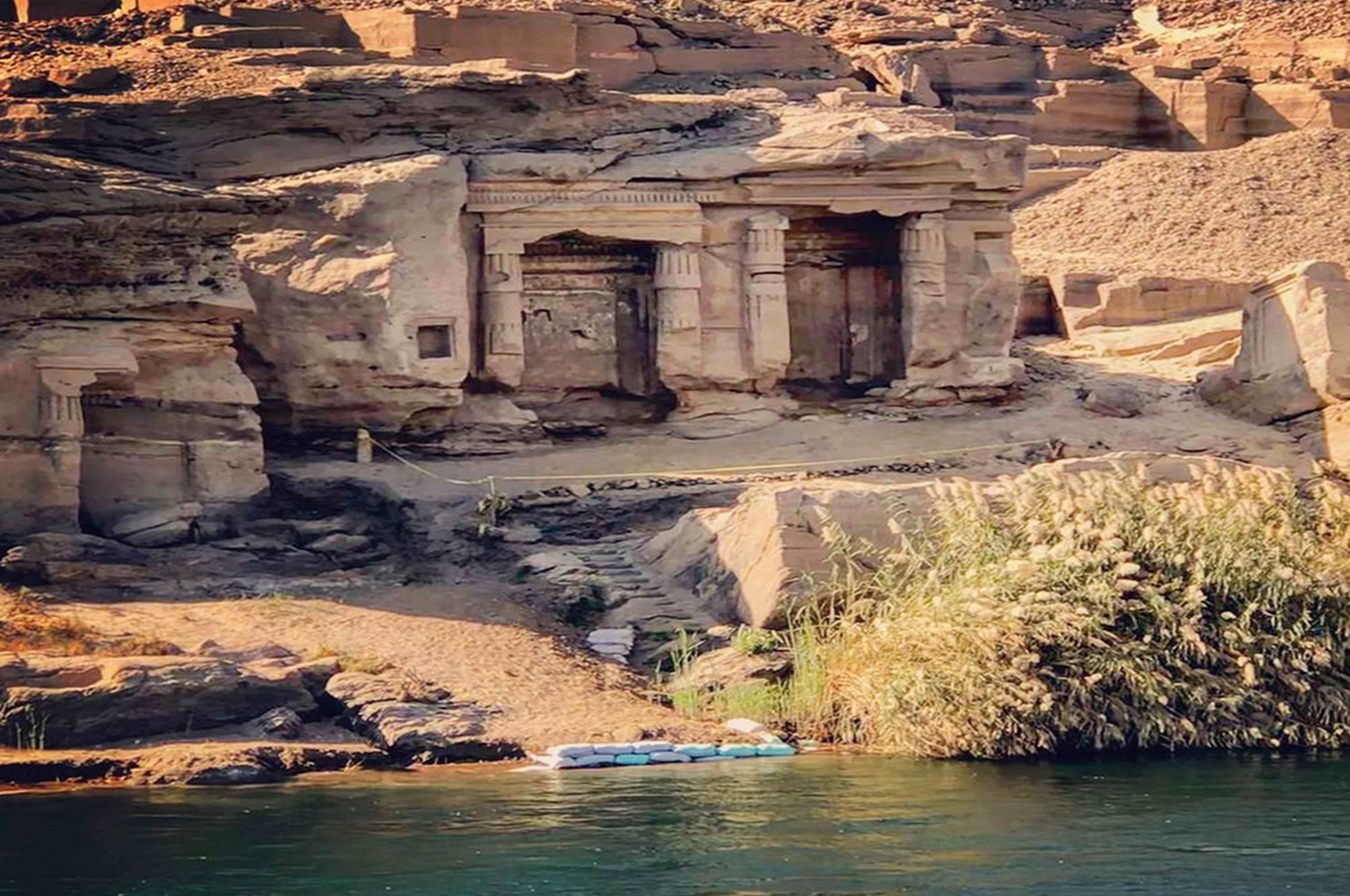

Gebel EL- Silsila West

The West Bank’s steep sandstone cliffs are strewn with graffiti, shrines, and stelae, including 33 rock chapels. Tuthmose I, Hatshepsut, Tuthmose III, and Horemheb built shrines in Dynasty XVIII, and Rameses II, Merenptah, Siptah, Seti II, Rameses III, and Rameses V had elaborate stelae carved on the rocks in Dynasty XIX. Seti I left an inscribed Hymn to the Nile and established two festivals that were continued by Rameses II and Merenptah. The most prominent deity depicted here appears to be Sobek the crocodile god, ‘Lord of Khennui,’ who is one of Kom Ombo’s twin gods with Haroeris (Horus the Elder). Hapi, the Nile’s god, also received a large share of offerings. Because of its proximity to Aswan, the Triad of Elephantine, Khnum, Satet, and Anuket was worshipped here. Tauret, the hippopotamus goddess, appears at Gebel Silsila, particularly in the Speos of Horemheb. Merenptah, Rameses II, and Seti I built three shrines (from north to south) on the west bank of the Nile, with a quay in front of them, but Seti’s shrine and the quay were destroyed by an earthquake. These shrines are now best accessed by boat. To the north, sheer quarried rock faces with mason’s marks, artisans’ drawings, and other evidence of ancient workings resemble sliced blocks of cheese. A rock-cut staircase leads up one side of these cliffs, but then vanishes, leaving you almost stranded. A rough rocky path, however, leads past ‘The Capstan’ and on to the royal shrines. The first monument is a large rock stele at right angles to the river that was built by Rameses III in Year VI of his reign. The first royal shine, like the other two, was built in the first year of Merenptah and was recessed deep into the rock behind two columns and a cornice. The inscription depicts a Hymn to the Nile and depicts the king worshipping various gods. To the south is a small Merenptah stele on which the king presents a figure of Ma’at to Amun-re. Vizier Panahesy and another official stand behind him. The second shrine dates from Rameses II’s early reign and depicts the king worshipping several deities. Queen Nefertari stands in front of a statue of the hippopotamus goddess Tauret, who is dressed in an unusual robe.A shrine is another small stele to Merenptah to the south of the Ramses, on which the King is joined by the High Priest of Amun, Roy. This stele is flanked by a small statue of King Amenhotep I. The shrines belonged to the time’s high officials, priests, royal scribes, and nobles. There is also a Dynasty XVIII tomb of Sennefer, a Theban libation priest who was buried here with his wife Hatshepsut. The tomb is now open to the sky, with the remains of five seated statues and hieroglyphic inscriptions visible near the water’s edge. There are three large rock stelae carved for Rameses V, Shoshenq I, and Rameses III at the northern end of the quarries (from north to south). One of Rameses V’s largest known monuments, the stele, contains an inscription dedicated to Amun-Re, Mut, Khons, and Sobek-Re of Khennui. Shoshenq’s stela describes how the king quarried here in year 21 of his reign for his building projects at Karnak. On Rameses III’s stele, the king is seen offering a ma’at statue to Amun-Re, Mut, and Khons.

Gebel Silsila East

The more spectacular Gebel Silsila quarries on the east bank of the Nile were most exploited during the New Kingdom, particularly under Rameses II, who employed three thousand workers to cut stone for the construction of the Ramesseum on the west bank at Thebes. Many shrines and stelae were carved into the rock here as well, and the names of the kings who worked in the quarries are attested by their officials, who provided detailed accounts of their work. The transport of stone for the construction of Ptah’s temple is documented in an inscription on a large stele of Amenhotep III. Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten, also has a stele here on which he worships Amun and records that he quarried stone for an obelisk to be erected in his Temple of the Sun at Karnak. Seti I and King Apries’ steles can also be seen. Several unfinished sphinxes, both ram and human-headed, remain rooted to the bedrock among the grottos and shelves of quarried sandstone. A number of small rock-cut tombs can be found at the foot of the hills. Rameses II constructed a temple at Gebel Silsila East, which has since been destroyed.

The Speos Of Horemheb

Horemheb, the final king of Dynasty XVIII, carved a much larger rock chapel, or Speos, out of the hillside at the site’s northern end. The chapel was dedicated to Amun-Re as well as other deities associated with the Nile. The monument is made up of five doorways separated by pillars of varying widths, with a long transverse hall with a vaulted roof behind it and a smaller oblong chamber, the sanctuary, to the rear. All of the walls are covered in reliefs and inscriptions, some of which are quite damaged, but there are some very fine high-quality reliefs in others. Oremheb never finished the Speos, and subsequent kings and nobles carved their own stelae and inscriptions on the walls to complete the decoration.

The Inscriptions

Aside from Amun-re, the deities depicted on the walls include Sobek as a crocodile, the ram-headed god Khnum of the First Cataract, Satet of Elephantine, Anuket, goddess of Sehel, Tauret as a hippopotamus, and Hapi, god of the Nile. Cartouches of Rameses II, Merenptah, Amenemesse, Seti II, Siptah, and Rameses III appear in the reliefs alongside those of Horemheb. The benevolent goddess Tauret is seen in rare human form on the southern end wall, suckling the young King Horemheb. A damaged figure of Khnum stands behind her, and Amun-Re and Sobek of Kennui stand to her left. The western wall depicts one of Horemheb’s most famous reliefs, the king’s ‘Triumphal Procession’ following his victory in Nubia. Horemheb is depicted sitting on a portable lion-chair, which is carried by twelve soldiers wearing feather plumes. The king’s fan-bearers stand in front and behind him, shielding him from the sun. Rows of priests, soldiers, a trumpeter, and several groups of captured prisoners are depicted in a very natural style, almost echoing some of the Amarna Period reliefs. The inscription above the king celebrates his victory over the Kush people. Another significant relief depicts a list of four Heb-sed festivals held by Rameses II during his reign in the 30th, 34th, 37th, and 40th years, which were overseen by his eldest son, Prince Khaemwaset. This prince, known for his priestly wisdom and restoration work, appears in several places throughout the chapel, alongside his mother, Queen Asetnefert, and Princess Bentanta, as well as other favoured officials of the reign. Khaemwaset most likely died before Rameses II’s 42nd Jubilee was celebrated at Gebel Silsila, as it was led by the Vizier Khay, who also has a presence in the Speos. Merenptah, Rameses II’s son and successor, is depicted on a stele adoring Amun-Re and Mut with his wife Asetnefert and his Vizier Panehesy. The Vizier Panehesy, the goddess Ma’at, a male relation Amennakht, a female relation ‘Songstress of Hathor,’ the god Ptah, and finally Ra’y, a female relation with the title ‘Songstress of Re’ are all depicted in high relief on the northern end wall. This is a rare relief depicting a private family in the presence of the gods. Many more stelae and reliefs line the hall’s walls, bearing the names of Dynasty XIX kings and officials. The sanctuary to the vaulted hall’s rear contains seven severely damaged figures said to represent Sobek, Tauret, Mut, Amen-Re, Khons, Horemheb, and Thoth. The reliefs on the side walls depict a wide range of gods and demi-gods, while the reliefs inside the doorway depict the Elephantine Triad, Khnum, Satet, and Anuket, as well as Osiris and the scorpion goddess Selkhet. Tauret rules over a symbolic representation of Upper and Lower Egypt’s union.