the land of the rising sun, the city of palaces, was one of ancient Egypt’s most important capitals for more than 1500 years. During the reign of the New Kingdom, the city flourished greatly, witnessing the construction of many astounding structures such as the Karnak Temple and the Luxor Temple. Luxor is known around the world as the largest open-air museum in the world, and it is said to house more than one-third of all historical sites on the planet. Luxor is divided into two sections: the West Bank of the Nile, also known as the city of the dead in ancient Egypt, and the East Bank of the Nile, also known as the city of the living. Luxor was known by many different names throughout its illustrious history. These names include Thebes as named by the ancient Egyptians, the city of the hundred doors in reference to the city’s large number of temples, and the city of a sceptre as a symbol of the rulers’ power. When the Arabs took control of Egypt in the middle of the 7th century, they were so impressed with Luxor and its monuments that they named the city Luxor or the City of the Palaces because of the massive structures built on its banks.

Due to the large number and diversity of Thebes’ historical sites, identifying specific monuments in Luxor would undoubtedly be a difficult task.

The highlights of Luxor include, in the East Bank; The Karnak Temple (The largest religious complex of the world, where it is believed that and average size European cathedrals can easily fit in), and The Luxor Temple, ” built over the reigns of many kings. Newly crowned pharaohs frequently demolished monuments erected by their forefathers, erecting their own with re-used blocks or over-carving reliefs in their own name (Luxor Museum was opened in 1975, displaying many artifact that tell the story of the glorious past of Luxor, in addition to the Mummification Museum, inaugurated on the year 1997 to document and illustrate the intricate mummification process of ancient Egyptian priests. The Valley of the Kings, the ancient necropolis of the kings of the dynasties from the 18th to the 20st centuries, where Howard Carter discovered the famous Tut Ankh Amun tomb in 1922, the Valley of the Queens, the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, the Ramssieum, the Mortuary Temple of Ramses II, the Valley of the Queens, the Colossi of Memnon, and the Mortuary temple of Ramsses III at Medinet Habu. This is in addition to some less visited monuments such as the Nobles’ Tombs and the Deir El Madina Necropolis, which was a community of expert workmen, sculptors, artists, architects, and scribes who lived in the west bank and practised unrivalled skills in the Nile Valley. Luxor rose to prominence in modern times as part of the ‘grand tour’ at the end of the nineteenth century. Many wonders were discovered in this ancient land by archaeologists, and wealthy European and American visitors flocked to Luxor as the first tourists.

Luxor Today, the modern town of Luxor has a thriving tourism industry, which accounts for a sizable portion of Egyptian revenue. The way of life on the West Bank’s scruffy back streets and alleyways, where the population ekes out a living from the land and the river, has remained largely unchanged. The Theban people are friendly and welcoming; their customs and hospitality have remained unchanged for hundreds of years, and it is easy to forget that the majority of them rely on tourism for a living. If you scratch the modern veneer, you will discover that the spirit of ancient Thebes lives on in Luxor. This spirit is what entices visitors to return and return again and again!

EXPLORE. CONNECT. CREATE MEMORIES

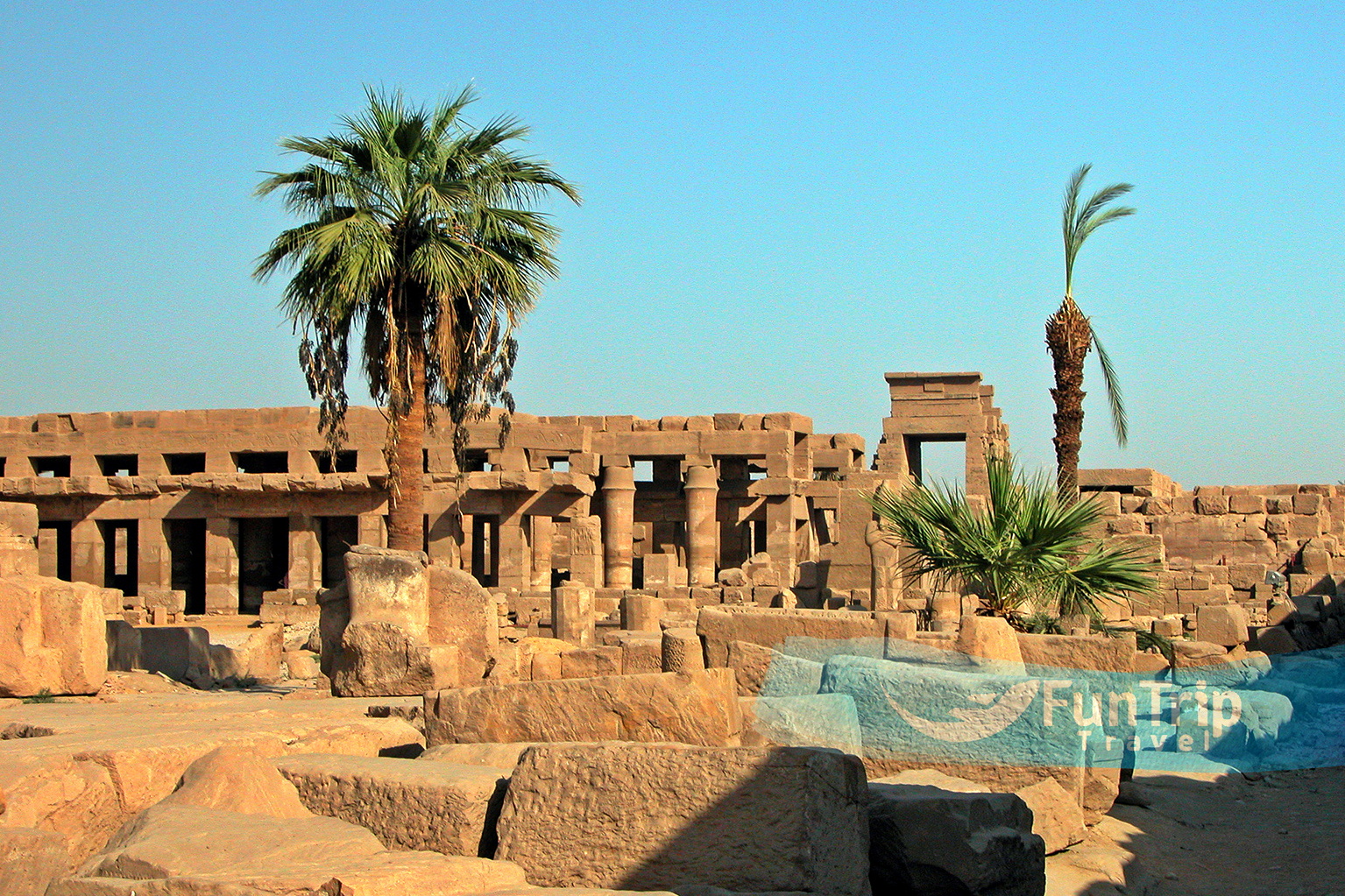

Amun Temple , Karnak Temple(Egypt’s Mysteries)

Amun-Ra was the local god of Karnak (Luxor), and during the New Kingdom, when the princes of Thebes ruled Egypt, he rose to prominence as the preeminent state god, with a temple to match. At its peak, the temple possessed 421,000 head of cattle, 65 cities, 83 ships, and 276,400 hectares of agricultural land, as well as 81,000 employees. The shell, sacked by Assyrians and Persians, is still one of the world’s great archaeological sites, grand, beautiful, and inspiring. During festivals, the large boats carrying the gods’ statues were moored at the Quay of Amun. We know from paintings in the tomb of Nakht and elsewhere that there were palaces to the north of the quay, surrounded by lush gardens. A ramp slopes down to the processional avenue of ram-headed sphinxes on the east side. These lead to the massive unfinished first pylon, the last to be built during Nectanebo I’s reign (30th dynasty). The massive mud-brick construction ramp, up which blocks of stone for the pylon were dragged with rollers and ropes, can still be seen on the pylon’s inner side. Napoleon’s expedition documented the remaining blocks on the ramp.

The Great Court

The largest area of the Karnak complex, is located behind the first pylon. To the left is the Shrine of Seti II, which houses three small chapels that housed Mut, Amun, and Khonsu’s sacred barques (boats) during the Opet Festival. The well-preserved Temple of Ramses III, a miniature replica of the pharaoh’s temple at Medinat Habu, is located in the southeastern corner (far right).The temple plan is straightforward and traditional: pylon, open court, vestibule with four Osirid columns and four columns, hypostyle hall with eight columns, and three barque chapels dedicated to Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. The only survivor of ten columns that once stood here is a 21m column with a papyrus-shaped capital and a small alabaster altar, all that remains of Taharka’s Kiosk, the 25th-dynasty Nubian pharaoh. Horemheb, the last 18th-dynasty pharaoh, began the second pylon, which was completed by Ramses I and Ramses II, who also erected three colossal red-granite statues of himself on either side of the entrance.

Great Hypostyle Hall

Beyond the second pylon is the amazing Great Hypostyle Hall, which is one of the most important religious buildings ever made. The hall is an amazing forest of 134 tall stone pillars that cover 5500 square meters. This is enough room to fit both St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Their papyrus shape represents a swamp, which was plentiful along the Nile. The ancient Egyptians believed that these plants surrounded the primordial mound where life first began. Each summer, when the Nile began to flood, this hall and its columns would fill with several feet of water. Originally, the columns would have been brightly painted (some color remains) and roofed, making it pretty dark away from the lit main axis. The size and grandeur of the pillars and the endless decorations can be overwhelming, so take your time, sit for a while, and stare at the dizzying spectacle.

Ramses I Designed the hall, which Seti I and Ramses II built. Note the difference in quality between Seti I’s delicate raised relief in the northern part of the hall and Ramses II’s much cruder sunken relief work in the southern part of the hall. The cryptic scenes on the inner walls were intended for the priesthood and royalty, who understood the religious context, but the outer walls are more easily understood, displaying the pharaoh’s military prowess and strength, as well as his ability to restore order to chaos. On the back of Amenhotep III’s third pylon, to the right, the pharaoh is shown sailing the sacred barque during the Opet Festival. Tuthmosis I (1504–1492 BC) built a narrow court between the third and fourth pylons, with four obelisks, two each for Tuthmosis I and Tuthmosis III (1479–1425 BC). Except for one 22-meter-tall base raised for Tuthmosis I, only the bases remain.

Inner Temple

To the right, on the back of Amenhotep III’s third pylon, the pharaoh is shown sailing the sacred baroque during the Opet Festival. Tuthmosis I (1504–1492 BC) built a narrow court between the third and fourth pylons, which housed four obelisks: two for Tuthmosis I and two for Tuthmosis III (1479–1425 BC). Nothing else remains except a 22-meter-high base built for Tuthmosis I. The ruined fifth pylon, which was built by Tuthmosis I, leads to another badly damaged colonnade. This is followed by the small sixth pylon, which was built by Tuthmosis III. He also built the two red-granite columns in the vestibule, which are carved with the symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt, the lotus and the papyrus. Nearby, on the left, are two massive statues of Amun and the goddess Amunet, carved during Tutankhamun’s reign. Tuthmosis III built the first Sanctuary of Amun, which was the center of the temple and where the god lived in the dark. When the Persians sacked the temple, it was destroyed and rebuilt in granite by Alexander the Great’s successor and half-brother, the frail, dim-witted Philip Arrhidaeus (323–317 BC). The Middle Kingdom Court, east of Philip Arrhidaeus’ shrine, is the temple’s oldest-known part, where Sesostris I built a shrine, the foundation walls of which have been discovered. The Wall of Records, which runs along the northern wall of the court, is a running tally of the organized tribute the pharaoh exacted in honor of Amun from his subjugated lands.

Great Festival Hall of Tuthmosis III

The Great Festival Hall of Tuthmosis III is located behind the Middle Kingdom Court. It’s an unusual structure with carved stone columns that look like tent poles, perhaps a nod to the pharaoh’s frequent military expeditions abroad, where he lived under canvas. The columned vestibule beyond, known as the Botanical Gardens, contains wonderful, detailed relief scenes of the flora and fauna that the pharaoh encountered and brought back to Egypt during his campaigns in Syria and Palestine.

Secondary Axis of the Amun Temple Enclosure

The cachette court is between the Hypostyle Hall and the seventh pylon. It got its name from the thousands of statues made of stone and bronze that were found here in 1903.Around 300 BC, the priests buried the old statues and temple furniture that they no longer needed. Most of the statues were taken to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, but there are still a few in front of the seventh pylon. On the left, there are four statues of Tuthmosis III. The eighth pylon, built by Queen Hatshepsut, is the oldest part of the temple’s north-south axis and one of Karnak’s earliest pylons. A text she falsely attributed to Tuthmosis I is carved on it, justifying her accession to Egypt’s throne.Herodotus says that the priests of Amun bathed twice a day and at night in the sacred lake, which is east of the seventh and eighth pylons. On the lake’s northwestern shore is a section of the fallen obelisk of Hatshepsut depicting her coronation, as well as a stone scarab dedicated by Amenhotep III to Khepri, a form of the sun god.

The Temple of Khonsu

God of the moon and son of Amun and Mut, is located in the enclosure’s southwest corner. It can be reached via a path through various blocks of stone from a door in the southern wall of the Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Amun. The temple, which was mostly built by Ramses III and later expanded by Ramesside rulers, is located north of Euergetes’ Gate and the avenue of sphinxes leading to Luxor Temple. The temple pylon leads to a hypostyle hall with eight columns carved with figures of Ramses XI and the High Priest Herihor, who ruled Upper Egypt at the time. The next chamber housed Khonsu’s sacred barque.

Deir Al Medina

The name of this site comes from a Ptolemaic temple that was later converted into a Coptic monastery, the Monastery of the Town, but the real draw is the one-of-a-kind Workmen’s Village. Many of the skilled workers and artists who built tombs in the Valleys of the Kings and Queens lived and died here. Archaeologists have discovered over 70 houses and many tombs in this village, with the most beautiful now open to the public. About 1km off the road to the Valley of the Queens and up a short, steep paved road, the small Ptolemaic-era temple, measuring only 10m by 15m, was built between 221 and 116 BC. It was dedicated to Hathor, the goddess of pleasure and love, and to Maat, the goddess of truth and personification of cosmic order. In front of the temple are the remains of the workers’ village, mostly low walls, although there are also remains of ancient irrigation pipes. More impressive, however, are the nearby tombs of Sennedjem, Peshedu, Inherka, and Ipuy. Originally, these were all topped by small mud-brick pyramids, one of which has been rebuilt.

Valley of the Queens

The tombs in the West Bank’s Valley of the Queens mostly belong to the 19th and 20th dynasties.

There are now nearly 80 tombs known, the majority of which were excavated between 1903 and 1905 by an Italian expedition led by E. Schiaparelli. Many of the tombs are unfinished and unadorned, resembling nothing more than caves in the rocks. There are few incised inscriptions or reliefs, and the majority of the decoration is in the form of paintings on stucco. Only four tombs are open to the public, but one of them is the famous Tomb of Queen Nefertari, which reopened in 2016, making a visit worthwhile. The tomb of Queen Nefertari, Ramses II’s wife, is considered the best of the West Bank’s tombs. The walls and ceilings of these chambers are adorned with dazzling, highly detailed, and richly colored scenes commemorating Nefertari’s legendary beauty. The Tomb of the Prince The best of the three tombs here is Amen-her-khopshef, which has well-preserved color wall paintings in its chambers.Amen-her-khopshef, Ramses III’s son, died as a teenager.Both the Tomb of Khaemwaset (another son of Ramses III) and the Tomb of Queen Titi have some interesting preserved scenes, though those in the Titi tomb are more faded than those in the Khaemwaset tomb. There is no agreement among archaeologists as to who Titi’s husband was.

Valley of the Kings

The west bank of Luxor had been used for royal burials since around 2100 BC, but it was the New Kingdom pharaohs (1550-1069 BC) who chose this isolated valley dominated by the pyramid-shaped mountain peak of Al Qurn (The Horn). The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Great Necropolis of Millions of Years of Pharaoh or the Place of Truth, is home to 63 magnificent royal tombs. The tombs have suffered greatly as a result of treasure hunters, floods, and, more recently, mass tourism: carbon dioxide, friction, and humidity produced by the average 2.8g of sweat left by each visitor have affected the reliefs and the stability of paintings made on plaster laid over limestone. In the worst-affected tombs, the Department of Antiquities has installed dehumidifiers and glass screens. The Theban Mapping Project website is the best source of information about the tombs, including detailed descriptions of their decoration and history. Some tombs charge additional admission fees and tickets. Tomb of Ay, Tomb of Horemheb (KV 57), Tomb of Ramses III (KV 11), Tomb of Ramses VI (KV 9) and Tomb of Seti I are among the highlights (KV 17).

They are listed in the order in which they were discovered.

Tomb of Ramses VII (1)

Ramses VII’s Tomb is a small, unfinished tomb. Due to the pharaoh’s unexpected death, it is much smaller, with only two chambers and a corridor, than many other tombs.

According to a Greek inscription, this tomb was known and accessible during the Ptolemaic period.

Tomb of Ramses IV (2)

The entrance to this tomb is reached via an ancient staircase with a ramp in the middle. On the door’s lintel, Isis and Nephthys are worshipping the sun, with the ram-headed sun god and a scarab depicted within.

Two figures of Copts raising their hands in prayer can be found on the right-hand entrance wall. One of them is “Apa Ammonios the martyr,” according to an inscription.

The scenes and inscriptions were painted on stucco, much of which has deteriorated. The pharaoh’s granite sarcophagus is covered with inscriptions and reliefs in the main chamber.

Tomb of Ramses IX (6)

This lovely tomb has some wonderful wall paintings.

The pharaoh is depicted in the presence of Harakhty and Osiris in the first corridor on the left-hand wall. A text from the Praising of Re can be found further along, above the doors of two small, undecorated chambers. A text from the 125th chapter of the Book of the Dead, just beyond the second chamber, contains a declaration by the dead man of his freedom from sin.The pharaoh is depicted in a chapel on the right-hand wall, surrounded by Amun and the death goddess Meretseger. Above the doors of the side chambers are depictions of snakes, dog- and bull-headed spirits, and an inscription that begins the “Sun God’s Journey through the Underworld.” In the second corridor, look to the left to see a snake rearing up in a vertical position. To the right of this and in the niche are figures of gods (from the Praising of Re), while below the niche is the king, followed by the goddess Hathor. Beyond this, on the left, are texts from the Book of the Dead and then a scene of the pharaoh in the presence of the falcon-headed Khons-Neferhotep, with a falcon hovering over his head.Look to the left in the second corridor to see a snake rearing up in a vertical position. Figures of gods (from the Praising of Re) are to the right of this and in the niche, while the king is below the niche, followed by the goddess Hathor. Texts from the Book of the Dead are on the left, followed by a picture of the pharaoh with the falcon-headed god Khons-Neferhotep and a falcon flying above his head. In the third corridor, the pharaoh gives an image of the goddess Maat to Ptah, who is standing in front of Maat herself. Beyond this, the pharaoh’s resurrection (his mummy lying on a hill with his arms raised above his head), with a scarab and the sun above the mummy, can be seen. From here, you enter the first chamber, which has a four-pillared roof. A short corridor leads down to the tomb chamber, which housed the sarcophagus. Figures of gods and spirits adorn the wall. The vaulted ceiling features two figures of the sky goddess, representing the morning and evening sky, with constellations and stellar bars beneath her.

Tomb of Merneptah (8)

Texts from the Praising of Re (on the left, a beautiful painted relief of the king before Re-Harakhty) and scenes from the Realm of the Dead (from the Book of the Gates) are painted on the walls of the entrance corridors. The corridors lead to an antechamber where the granite lid of the outer coffin is kept. Steps descend from here to a three-aisled hypostyle hall with a barrel vault over the central aisle and flat roofs over the side aisles. The lid of the royal sarcophagus, depicting a recumbent pharaoh, is housed in this chamber. The lid, which is shaped like a royal cartouche, is beautifully carved in pink granite. The carving of the pharaoh’s face is especially good.

Tomb of Ramses VI (9)

This tomb was built for Ramses V. It is known for how well its painted sunk reliefs have been kept, even though their style isn’t as good as those from the 19th Dynasty.Three corridors lead into an antechamber, which leads to the first pillared chamber of Ramses V’s tomb. The left-hand walls depict scenes from the Book of the Gates depicting the sun’s journey through the Underworld.Two corridors with scenes from the sun god’s journey through the Underworld according to the Book of What Is in the Underworld lead into another antechamber with texts and scenes from the Book of the Dead covering the walls. After this is the second pillared chamber, which still has parts of the big granite sarcophagus.Texts about the underworld can be found on the walls, and two figures of the sky goddess, representing the day sky and the night sky, with the hours, can be found on the vaulted ceiling. Numerous Greek and Coptic graffiti can be found on the tomb.

Tomb of Ramses III (11)

Although the reliefs are not particularly well executed, they are notable for their variety and excellent color preservation. The goddess Maat is kneeling in the first corridor, to the right and left of the entrance, sheltering those who enter the tomb with her wings.Look up to the upper row of scenes on the left in the third side chamber to see a kneeling Nile god bestowing gifts on seven fertility gods (with ears of corn on their heads).The fourth side chamber, on the right, served as the pharaoh’s armory and features wall paintings of the sacred black bull Meri on the “Southern Lake” (on the left) and the black cow Hesi on the “Northern Lake” (on the right).The fourth corridor depicts the sun’s journey during the fourth hour of the night. This leads to the sixth chamber, which has a sloping passage with side galleries and four pillars depicting the pharaoh in the presence of various gods.The walls on the left (starting with the entrance wall) depict the sun’s journey through the fourth part of the Underworld (Book of the Gates), while the walls on the right depict the sun’s journey through the fifth part of the Underworld (Book of the Gates).On the right side of the seventh chamber, you can see the pharaoh being led by Thoth and Harkhentekhtai, who has a falcon’s head. On the left side, you can see the pharaoh giving an image of Truth to Osiris.The pharaoh’s sarcophagus once stood in the tenth room. His mummy was discovered at Deir el-Bahri and is now housed in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum.

Tomb of Tausert & Setnakht (14)

This is one of the Valley of the Kings’ largest double tombs.

It was designed for Tausert, the wife of Seti II, who ruled for the final two years of the 19th Dynasty. The tomb was thought to have been built for both her and Seti II, but it was taken over by her immediate successor, Pharaoh Setnakht, who expanded it, tunnelling deeper into the ground to create a burial chamber for himself. Setnakht also made changes to the tomb’s decoration, and original paintings depicting Tausert in the lower reaches of the tomb complex were later replaced by scenes depicting Setnakht. The highlight here is Tausert’s burial chamber, which is dominated by a large scene depicting a winged and ram-headed sun god emerging from the underworld.

Tomb of Seti II (15)

Setnakht most likely built Seti II’s tomb after deciding to take the pharaoh’s original burial place for himself. This tomb is much smaller than the nearby Tombs of Tausert and Setnakht. The decorative work here lacks the attention to detail found in other tombs, and because the tomb has been open since antiquity, Greek and Latin graffiti can be found on the chamber and corridor walls. The best wall reliefs can be found near the tomb’s entrance, and the upper reaches of the sloping corridor depict scenes from the Litany of Ra. The stone sarcophogus remains in Seti II’s burial chamber.

Tomb of Ramses I (16)

This tomb is currently closed to the public.A sloping corridor and a steep staircase lead down to the tomb chamber, which contains the open red granite coffin of the king, with pictures and texts painted in yellow.The walls of the chamber are decorated with colorful scenes and inscriptions.Look to the left of the entrance wall to see Maat and Ramses I before Ptah. To the right, Maat and the pharaoh are making an offering to Nefertum, while behind them is the Isis knot.Scenes from the third section of the Book of the Gates can be found on the left-hand wall to the right of the door and above it. The journey through the third division of the underworld begins with the gateway, which is guarded by a snake. The boat is being drawn by four men in the center towards a long chapel containing the mummies of nine gods.

Tomb of Seti I (17)

Seti I’s tomb is also known as Belzoni’s tomb because it was opened by Belzoni in October 1817.Most of the reliefs in the Valley of the Kings are not as well kept or as well made as these.It was closed to visitors for years due to preservation issues, but it has recently reopened as one of the Valley of the King’s main attractions.The first pillared chamber depicts scenes from the sun’s journey through the fourth division of the underworld (the fourth part of the Book of the Gates).The fourth gateway is guarded by a snake at the beginning, followed by the solar barque drawn by four men in the middle row and spirits with a coiled snake, three ibis-headed gods, and nine other gods in front of it (“the spirits of men who are in the Underworld”).A flight of 18 steps leads down from the first pillared chamber through two corridors depicting the “opening of the mouth” ceremony into an antechamber with fine reliefs of the pharaoh in the presence of various gods of the dead.The second pillared chamber is reached via a short flight of steps. In this room, the scenes and inscriptions are simply scribbled in red and black on stucco.The pharaoh is depicted on the pillars in front of various deities. The scenes on the back wall depict the path of the sun during the tenth hour of the night (10th part of the Book of What Is in the Underworld).A ramp flanked by steps leads down to the mummy shaft from the third pillared chamber. This consists of a front portion with six pillars and a lower-level rear portion with a vaulted roof.The front section contains scenes from the Book of the Gates depicting the realm of the dead. The pharaoh’s alabaster sarcophagus, now in the Soane Museum in London, was in the back section. The king’s body was found in Deir el-Bahri, and it is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Tomb of Tuthmosis III (34)

Tuthmosis III’s tomb is located 250 meters south of Ramses III’s tomb in a narrow and steep-sided gully. This tomb is not currently accessible to the public. A sloping corridor down to a staircase with wide niches on the right and left leads to a square shaft five to six meters deep, probably intended to deter tomb robbers; it is now crossed by a footbridge. The roof is decorated with white stars on a blue background.Beyond the shaft is a chamber with two pillars and lists of 741 different deities and demons on the walls. A staircase at the left end of the back wall leads down to the tomb chamber, which has the oval shape of a royal cartouche. Two square pillars support the ceiling, which has yellow stars on a blue background.The walls are covered in well-preserved scenes and passages from the Book of the Underworld. Those on the pillars are especially interesting.The first pillar has a long religious text on one side and Tuthmosis III and his mother in a boat (at the top) and the king being suckled by his mother in the form of a tree on the other (below).The sarcophagus is made of red sandstone and is decorated with painted scenes and inscriptions. The tomb was empty when it was opened, but the mummy was discovered at Deir el-Bahri. The grave goods from the four small side chambers are now housed in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum.

Tomb of Amenophis II (35)

Steep flights of steps and sloping corridors descend from the entrance to a shaft (now bridged over), at the foot of which is a small room, and beyond this is the first chamber (undecorated) with two pillars. This tomb is not currently accessible to the public.A flight of steps at the left end of the back wall leads down to a sloping corridor, at the end of which is the second chamber with six pillars. A crypt is located to the rear of this chamber, on a lower level.The king is depicted on the pillars in the presence of the gods of the dead, while scenes and texts from the Book of What Is in the Underworld are finely executed on the walls.The crypt contains the king’s sandstone sarcophagus, in which Amenophis II’s mummy was discovered intact with a bouquet of flowers and garlands.On each side are two chambers where many mummies were discovered, no doubt brought here to avoid tomb robbers, including those of Tuthmosis IV and Amenophis III (18th Dynasty) and Siptah and Seti II (19th Dynasty).

Tomb of Tutankhamun (62)

The Tomb of Tutankhamun, discovered by Howard Carter on November 4, 1922, is by far the Valley of the Kings’ most famous tomb. Tutankhamun was Akhenaten’s son-in-law and died (under unknown circumstances) in his 18th or 19th year. Even though the tomb was broken into soon after the pharaoh was buried, almost everything was still there, like the pharaoh’s expensive furniture. These furnishings, known as the “Treasures of Tutankhamun,” were the largest and most valuable finds of grave goods ever made in Egypt, giving an overwhelming impression of the splendor of a royal burial in pharaonic times. Tuthmosis IV and Amenophis III (18th Dynasty), as well as Siptah and Seti II (19th Dynasty), A flight of 16 steps leads down to the tomb’s east side entrance. The doorway leads into a narrow 7.5-meter-long passage, and at the far end, another door leads to an antechamber, the largest chamber in the tomb, which was discovered filled to the brim with grave goods of all kinds. A side chamber can be found in the southwest corner (far left). Two life-size wooden pharaoh statues were discovered on the north wall. The sarcophagus, made of yellowish crystalline sandstone, sits in the center of the chamber. Its sides are covered with religious scenes and texts, and the corners feature four relief figures of goddesses with protective wings outspread. Inside the sarcophagus, the pharaoh’s mummy was housed in three richly decorated wooden coffins. A small storeroom can be found on the east side of the tomb chamber. On the walls of the chamber are painted scenes depicting Tutankhamun’s successor, Pharaoh Ay, performing the “opening of the mouth” ceremony on the mummy and Tutankhamun making offerings to various gods.

Tomb of Ay (23)

The Tomb of Ay (Tutankhaman’s Successor) is located outside the main valley of the Kings tomb area, in the West Valley, about a two-kilometer walk west of the main valley of the Kings visitor’s center. Most visitors overlook it because of its isolation from the other open tombs. You are very likely to have the tomb to yourself, which, combined with the barren beauty of the surrounding cliffs and the lack of tour buses on the walk here, is one of the main reasons to visit. The only decoration inside the tomb is in the burial chamber. The corridors are simple. The burial chamber paintings, on the other hand, are notable among royal tombs for depicting scenes from everyday life. Pharaoh Ay is shown fishing in one scene and hunting hippos in another. There is also a large baboon wall painting.

Necropolis of the Pharaohs

The valley was named after the lavishly furnished tombs built here for the pharaohs of the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties. In contrast to the previously popular pyramid tombs, these tombs are made up of a series of passages and chambers hewn from the rock. As with the chambers inside the pyramids, these were only meant to hold the sarcophagus. In the plain, temples dedicated to the cult of the dead pharaohs were built. The tombs typically have three corridors leading into their deepest recesses. The third corridor leads to an antechamber, which leads to the main chamber, which has a pillared roof and a cavity in the floor where the heavy granite sarcophagus was deposited. Several subsidiary chambers adjoin the main chamber. Because it was believed that the dead man sailed through the Underworld at night in a boat, accompanied by the sun god (or perhaps having become one with the sun god), the walls of the tombs were frequently adorned with texts and scenes depicting this voyage and giving the dead man instructions on its course. The scenes and texts were mostly taken from two books that are closely related. The first is the Book of What Is in the Underworld, which has 12 chapters because the Underworld (Duat) was thought to be divided into 12 parts or caverns, each corresponding to one of the twelve hours of the night. Each of these scenes is centered on a river, on which the ram-headed sun god and his train sail in the solar barque, briefly dispensing light and life. The riverbanks, both above and below, are populated by spirits, demons, and monsters who greet and defend the sun god as he passes. The second book, known as the Book of the Gates, also deals with the sun’s nocturnal journey through the Underworld’s 12 sections. Massive gates guarded by giant snakes whose names the dead man must know separate these sections. The approach is guarded by two gods and two fire-breathing snakes, who greet the sun god. In other ways, the Underworld concept is similar to that of the first book. The Sun God’s Journey Through the Underworld is a third work. It shows the sun god speaking to the spirits and monsters of the underworld, who are depicted in long rows. The Praising of Re (or Litany of Re) and the Book of the Opening of the Mouth were also used to decorate the tomb walls. The former, which can be found in the first two corridors, is a hymn to the sun god, whom the deceased had to invoke under 75 different names when he entered the Underworld in the evening. The latter teaches the various ceremonies that had to be performed in front of the statue of the dead man in order for it to eat and drink what was left for it in the tomb.

Medinet Habu

Medinat Habu, Ramses III’s beautiful memorial temple, is one of the most underrated places on the west bank. It is in front of the quiet village of Kom Lolah, and the Theban mountains are in the back.This was one of the first places in Thebes where the god Amun was worshipped in a big way.Medinat Habu had temples, storage rooms, workshops, administrative buildings, a royal palace, and housing for priests and officials at its peak. For centuries, it was the epicentre of Thebes’ economic life. Although Ramses III’s funerary temple is the most famous structure in the complex, Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III also built structures here. They were later supplemented and altered by a succession of rulers, up to and including the Ptolemies. When pagan cults were outlawed, it became an important Christian center and remained inhabited until the 9th century AD, when a plague was thought to have decimated the town. On top of the enclosure walls, you can still see the mud-brick remains of the medieval town that gave the site its name (medina means “town” or “city”). Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III built the first Temple of Amun, but later, Ramses III’s huge Funerary Temple, which is the most important part of Medinat Habu, completely covered it up.However, a chapel from the Hatshepsut period can still be found on the right after passing through the outer gates. Ramses III got the idea for his shrine from the Ramesseum, which was built by his famous father, Ramses II.Both his temple and the smaller one for Amun are surrounded by the huge walls that surround the whole complex. The Tomb Chapels of the Divine Adorers, which were built for Amun’s principal priestesses, are also just inside, to the left of the gate. A landing quay for a canal that once connected Medinat Habu with the Nile was located outside the eastern gate, one of only two entrances. You enter the site through the unique Syrian Gate, a large two-story building modelled after a Syrian fortress. This, like the images of the pharaoh smiting his enemies, recalls the famous battles between Egyptians and Hittites, particularly during Ramses II’s reign. A staircase leading to the upper floors can be found by following the wall to the left. The rooms are small, but the views out across the village in front of the temple and over the fields to the south are spectacular. The front of the temple proper is marked by the well-preserved first pylon. In its reliefs, Ramses III is depicted as the victor of several wars. The fine reliefs depicting his victory over the Libyans are the most famous (whom you can recognize by their long robes, sidelocks, and beards). A gruesome scene depicts scribes counting severed hands and genitals to determine the number of enemies killed. The remains of the Pharaoh’s Palace are to the left of the first court; the three rooms at the back were for the royal harem. The Window of Appearances, located between the first court and the Pharaoh’s Palace, allowed the pharaoh to show himself to his subjects. Ramses III is depicted in the reliefs of the second pylon presenting prisoners of war to Amun and his vulture goddess wife, Mut. The second court is surrounded by colonnades and reliefs depicting various religious ceremonies. If you have time to explore the extensive ruins surrounding the funerary temple, you will find the remains of an early Christian basilica, a small sacred lake, and the outline of the palace and the window looking into the temple courtyard, where Ramses would appear. It’s a beautiful spot to visit, especially late in the afternoon when the light softens and the creamy stone glows.

Luxor Temple

This temple, which was largely constructed by the New Kingdom pharaohs Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC) and Ramses II (1279–1213 BC), is a strikingly graceful monument in the heart of the modern town. Its main function was during the annual Opet celebrations, when the statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu were transported from Karnak along the Avenue of Sphinxes and reunited here during the inundation. Visit early in the morning before the crowds arrive or later in the evening when the stones glow. Return at night when the temple is illuminated, creating an eerie spectacle as shadow and light play off the reliefs and colonnades. Hatshepsut had already built a shrine, but Amenhotep III made it much bigger and gave it a new name: Amun’s southern ipet (harem), or the god’s private quarters. Tutankhamun, Ramses II, Alexander the Great, and various Romans added to the structure. The Romans built a military fort around the temple, which the Arabs later called Al Uqsur (The Fortifications), which was later corrupted to become the name of modern Luxor. In ancient times, the temple would have been surrounded by a maze of mud-brick houses, shops, and workshops, which now lie beneath the modern town, but after the city declined, people moved into the by then partly covered temple complex and built their city within it. In the 14th century, a mosque was built in one of the interior courts for the local sheikh (holy man), Abu Al Haggag. Excavation work began in 1885, clearing away the village and centuries of debris to reveal what can be seen of the temple today, but the mosque remains and has been restored after a fire. The temple is less complex than Karnak, but here again you walk back in time the deeper you go into it. In front of the temple is the beginning of the Avenue of Sphinxes, which ran all the way to the temples at Karnak, 3km to the north, and is now almost entirely excavated. Ramses II erected the massive, 24 m-high first pylon, which was adorned with reliefs depicting his military exploits, including the Battle of Kadesh. The pylon was originally flanked by six colossal statues of Ramses II, four seated and two standing, but only two seated and one standing figure remain. One of the original pair of pink-granite obelisks that stood here still stands, while the other is in Paris’ Place de la Concorde. Beyond that is Ramses II’s Great Court, which is surrounded by a double row of columns with lotus-bud capitals and whose walls are decorated with scenes of the pharaoh making offerings to the gods. On the south (back) wall, there is a picture of 17 of Ramses II’s sons, along with their names and titles. The older triple-barque shrine for Amun, Mut, and Khonsu was built by Hatshepsut and then taken over by her stepson Tuthmosis III. It is in the northwest corner of the court. The Abu Al Haggag Mosque, which was built in the 14th century and is dedicated to a local sheikh, can be reached from Sharia Maabad Al Karnak, which is outside the temple, and hangs over the southeast side. Beyond the court is the older and more beautiful Amenhotep III Colonnade. It was built as the main entrance to the Temple of Amun of the Opet. During the young pharaoh Tutankhamun’s reign, the walls behind the elegant open papyrus columns were decorated to mark the return to Theban orthodoxy after Akhenaten’s unorthodox rule. The Opet Festival is shown in great detail, with the pharaoh, nobles, and common people all marching in triumph. Look out for the drummers and acrobats doing backbends. The Sun Court of Amenhotep III is south of the Colonnade. It used to be surrounded on three sides by double rows of tall papyrus-bundle columns. The columns on the eastern and western sides are the best preserved, with their architraves still in place.

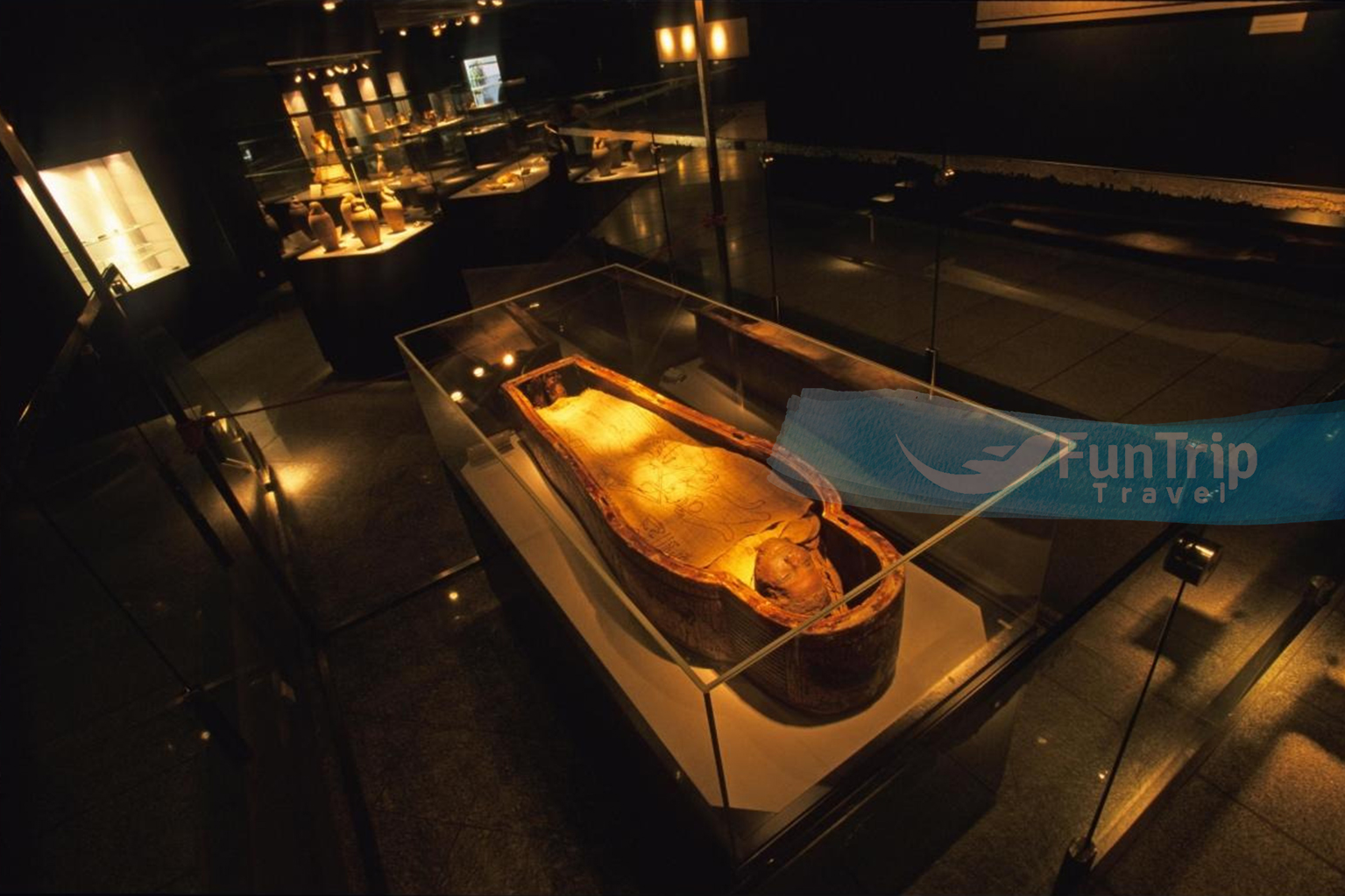

The Luxor Museum

This wonderful museum has a well-chosen, beautifully displayed, and well-explained collection of artifacts from the end of the Old Kingdom to the Mamluk period, most of which come from Theban temples and necropolises. The ground-floor gallery has several masterpieces, including a well-preserved limestone relief of Tuthmosis III (No. 140), an exquisitely carved statue of Tuthmosis III in graywacke from the Temple of Karnak (No. 2), an alabaster figure of Amenhotep III protected by the great crocodile god Sobek (No. 155), and one of the few examples of Old Kingdom art found at Thebes, a relief of Unas-ankh (No. 183), found in his tomb on the west bank. In 2004, a new wing was dedicated to Thebes’ glory during the New Kingdom period. The two royal mummies, Ahmose I (founder of the 18th dynasty) and the mummy some believe to be Ramses I (founder of the 19th dynasty and father of Seti I), are beautifully displayed without their wrappings in dark rooms and are the main reason for the new construction. Other well-labelled displays depict Thebes’ military might during the New Kingdom, Egypt’s empire-building period, including chariots and weapons. The military theme is diluted on the upper floor by scenes from daily life depicting New Kingdom technology.Workers harvest papyrus and process it into sheets for writing on multimedia displays. Young boys are shown reading and writing hieroglyphs alongside a display of scribes’ and architects’ tools. Moving up the ramp to the first floor of the old building, you come face to face with a seated granite figure of the legendary scribe Amenhotep (No. 4), son of Hapu, the great official eventually deified in Ptolemaic times and who, as overseer of all the pharaoh’s works under Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC), was responsible for many of Thebes’ greatest buildings. The Wall of Akhenaten, a series of small sandstone blocks named talatat (threes) by workmen, probably because their height and length were about three hand lengths, that came from Amenhotep IV’s contribution at Karnak before he changed his name to Akhenaten and left Thebes for Tell Al Amarna, is one of the most interesting exhibits. His building was demolished, and in the late 1960s, approximately 40,000 blocks used to fill in Karnak’s ninth pylon were discovered and partially reassembled here. The scenes depicting Akhenaten, his wife Nefertiti, and temple life are a rare example of Aten temple decoration. Treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb are also on display. These include shabti (servant) figures, model boats, sandals, arrows, and a set of gilded bronze rosettes from his funeral pall. You can go back down to the ground floor on a ramp, which puts you near the exit and next to the black-and-gold wooden head of the cow deity Mehit-Weret, which was found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. It is an aspect of the goddess Hathor. A small hall on the left, just before the exit, houses 16 of the 22 statues discovered in the Luxor Temple in 1989. All are magnificent examples of ancient Egyptian sculpture, but at the far end of the hall stands a nearly pristine 2.45-meter-tall quartzite statue of a muscular Amenhotep III dressed in a pleated kilt.

Temple of Hatshepsut

At Deir Al Bahri, the eyes are drawn to the dramatic, rough limestone cliffs that rise nearly 300 meters above the desert plain. However, at the base of all this amazing beauty is an even more amazing monument: the dazzling Temple of Hatshepsut. The almost modern-looking temple blends in beautifully with the cliffs from which it is partially cut—a perfect marriage. The majority of what you see has been painstakingly rebuilt. Since 1891, continuous excavation and restoration have revealed one of ancient Egypt’s finest monuments. It must have been even more beautiful in the days of Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BC), when it was approached by a grand sphinx-lined causeway rather than today’s noisy tourist bazaar, when the court was a garden planted with exotic trees and perfumed plants, and when it was linked to the Temple of Karnak across the Nile. Senenmut, a courtier at Hatshepsut’s court and possibly her lover, designed the Djeser-desert (the Most Holy of Holies). If the design seems strange, keep in mind that it had all the typical parts of a memorial temple, like a rising central axis and a three-part plan. However, it had to be changed to fit the site, which was almost exactly on the same line as the Temple of Amun at Karnak and close to an older shrine to the goddess Hathor.Tuthmosis III got rid of any mentions of his stepmother; Akhenaten got rid of all references to Amun; and early Christians turned it into a monastery called Deir Al Bahri (Monastery of the North) and covered up the reliefs of the gods. Deir Al Bahri has been designated as one of the hottest places on the planet, so visiting early in the morning is recommended, as the reliefs are best seen in low light. The complex is entered through the great court, where the original ancient tree roots can still be seen. At the time of writing, the colonnades on the lower terrace were closed for restoration. On the south colonnade, to the left of the ramp, there is a delicate relief of Hatshepsut’s obelisks being moved from Aswan to Thebes. On the north colonnade, there are scenes of birds being caught. The two upper terraces are accessible via a large ramp. The reliefs on the middle terrace are the best preserved. The reliefs on the north colonnade commemorate Hatshepsut’s divine birth, and at its end is the Chapel of Anubis, which contains well-preserved, colorful reliefs of a disfigured Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III in the presence of Anubis, Ra-Horakhty, and Hathor. The wonderfully detailed reliefs in the Punt Colonnade to the left of the entrance tell the story of an expedition to the Land of Punt to collect myrrh trees needed for temple incense. There are pictures of strange animals and plants, as well as buildings and landscapes from other countries and people with strange looks. The Hathor Chapel, at the end of this colonnade, has two chambers, both with Hathor-headed columns. Reliefs on the west wall, which you can see with a flashlight, show Hathor as a cow licking Hatshepsut’s hand while the queen drinks from Hathor’s udder. A faded relief of Hatshepsut’s soldiers dressed as sailors pays tribute to the goddess on the north wall.A three-roomed chapel cut into the rock beyond the pillared halls is now closed to the public, with reliefs of the queen in front of the deities and, behind the door, a small figure of Senenmut, the temple’s architect and, some believe, Hatshepsut’s lover. The upper terrace, which was restored over the last 25 years by a Polish-Egyptian team, had 24 colossal Osiris statues, some of which are still standing. The central pink-granite doorway leads into the hewn-out-of-the-cliff Sanctuary of Amun.On the south side of Hatshepsut’s temple are the ruins of the Temple of Montuhotep, which was built for the founder of the 11th dynasty and is one of the oldest temples found in Thebes, and the Temple of Tuthmosis III, who came after Hatshepsut. Both are in ruins.

Colossi of Memnon

The two faceless Colossi of Memnon, which originally represented Pharaoh Amenhotep III and rise majestically about 18 metres above the plain, are the first monuments tourists see when they visit the west bank. These magnificent colossi, each carved from a single block of stone and weighing 1000 tonnes, stood at the eastern entrance to Amenophis III’s funerary temple, the largest on the west bank. Egyptologists are currently excavating the temple, with their findings visible behind the colossi. During Graeco-Roman times, the colossi were a popular tourist attraction because they were attributed to Memnon, the legendary African king who was slain by Achilles during the Trojan War. The whistling sound emitted by the northern statue at sunrise was thought to be the cry of Memnon greeting his mother Eos, the goddess of dawn, by the Greeks and Romans. She, in turn, would cry dewy tears for his untimely death. All of this was most likely caused by a crack in the colossus’ upper body that appeared after the earthquake of 27 BC. As the morning sun baked the dew-soaked stone, sand particles would break off and resonate inside the structure’s cracks. Memnon’s plaintive greeting was no longer heard after Septimus Severus (193-211 AD) repaired the statue in the third century AD. The colossi are located just off the road, before reaching the Antiquities Inspectorate ticket office, and are frequently photographed and filmed by a swarm of tourists. Few visitors realise that these massive enthroned figures are set in front of the main entrance to an equally impressive funerary temple, Egypt’s largest, the remains of which are slowly being revealed. Some tiny remnants of the temple that stood behind the colossi remain, and more is being unearthed as the excavation continues. Many statues were later dragged off by other pharaohs, including the massive dyad of Amenhotep III and his wife Tiye, which now dominates the central court of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, but much still remains beneath the silt. The temple was built of ‘white sandstone, with gold throughout, a floor covered with silver, and doors covered with electrum,’ according to a stele now housed in the Egyptian Museum. No gold or silver has yet been discovered, but a large area littered with statues and masonry that had long lain beneath the ground can be seen if you walk behind the colossi.

Mummification Museum

The Mummification Museum, housed in a former visitors centre on Luxor’s corniche, has well-presented exhibits explaining the art of mummification. The museum is small, and the admission fee may be considered excessive by some. Furthermore, despite the fact that it should be open all day, a lack of visitors causes it to close for several hours after midday. The well-preserved mummy of Maserharti, a 21st-dynasty high priest of Amun, and a slew of mummified animals are on display. The tools and materials used in the mummification process are displayed in vitrines, such as the small spoon and metal spatula used to scrape the brain out of the skull. Several artefacts important to the mummy’s journey to the afterlife have also been included, as have some beautiful painted coffins. A beautiful little statue of the jackal god, Anubis, the god of embalming who assisted Isis in turning her brother-husband Osiris into the first mummy, presides over the entrance.