The ancient city of Bahariya, also known as the “Northern Oasis,” is in a depression 100 (km) long and 40 (km) broad, and it is encircled on all sides by towering black escarpments.

Being just 365 km from Cairo, it is one of the more approachable oasis towns on the desert circuit. Forests of date palms cover most of the oasis floor, which is pocked with hundreds of cooling springs and hemmed in on all sides by rocky, sandy mesas.

The valley floor is dotted with various conical hills that were once islands in a large lake, and it is blanketed in lush forests of date palms, old springs, and wells. Being an agricultural hub, the oasis supplied the Nile Valley and even Rome with wine during the Pharaonic era. Long-term success was guaranteed by the city’s placement on the caravan routes connecting Libya and the Nile Valley. Bahariya has risen in popularity as a tourist destination in recent years because to its proximity to the White and Black Deserts and its stunning golden mummies.

El Bawiti, the most populous hamlet in Bahariya and the city’s administrative hub, is only one among several. A sister community of el-Bawiti, Qasr sits close by. 10 kilometres to the east are the small towns of Mandishah and el-Zabu. The little community of el-‘Aguz may be found between El Bawiti and Mandishah. Harrah, the farthest eastern settlement, is just a little distance east of Mandishah and el-Zabu. El Hayz (also spelled El-Hayez) is the most southern settlement, although its isolation, some fifty kilometres south of El Bawiti, means that it isn’t generally included in Bahariya.

An oasis in El-Hayez has yielded mummies and allowed for genetic research.

The Bedouin tribes from Libya and the north coast, as well as other residents from the Nile Valley, settled in the oasis thousands of years ago, leaving behind their ancestors, the Wahat (which means “of the oasis” in Arabic).

The majority of Bahariya’s Wat population are Muslims. A small number of mosques may be found in Bahariya. Communities in the oasis are heavily influenced by Islamic culture.

The Wat people place a high value on traditional music as well. Flute, drum, and simsimeyya (a harp-like instrument) are often performed at social events like weddings. New songs, as well as old ones performed in a traditional country way, are handed down from generation to generation. Residents of the oasis may now listen to songs from Egypt, the Middle East, and beyond.

EXPLORE. CONNECT. CREATE MEMORIES

Gebel Dist

is a large peak fashioned like a pyramid, visible from much of the oasis. Dinosaur bones were unearthed there in the early 20th century, demonstrating that these creatures did not originate from North America as was previously believed. Paralititan stromeri fossils, from 2001, were found by University of Pennsylvania scientists.

The fact that this huge herbivore was found at the border of a tidal channel leads the experts to believe that Bahariya was once a swamp like the Florida Everglades in the United States, some 94 million years ago. Around a hundred metres distant lies Gebel Maghrafa (the Mountain of the Ladle).

Gebel Al Ingleez

The real reason to come here is for the spectacular panoramic views that extend across the oasis and into the desert beyond.

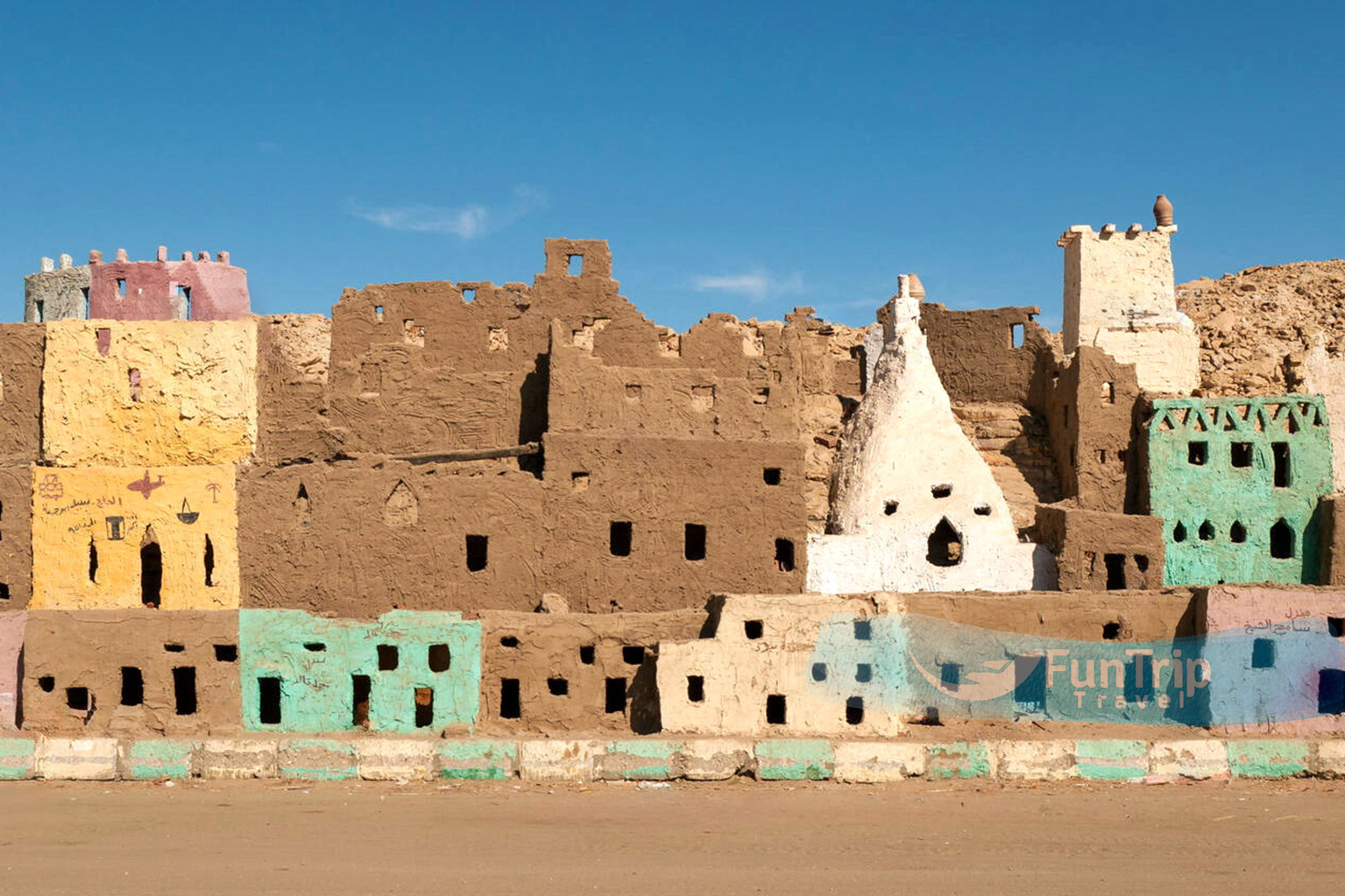

Bawiti

Is a modern settlement surrounded by historic landmarks. Indeed, Bawiti serves as Bahariya’s administrative centre. Now that the oasis is well-known thanks to the “Valley of the Golden Mummies” discovery, tourists and visitors are welcome to explore the area’s other historic sites.

A modest museum housed in what was formerly a warehouse may be found at the far rear of the Antiquities Department. It is home to five exceptionally preserved Greek and Roman mummies and a few other noteworthy artefacts from the Bahariya Oasis.

The Unique Aqueduct System In Bwaiti

In the alleys of Bawiti, you can still see the remnants of the old manafis aqueduct system. From Bawiti, you may reach the gardens and the Ain El-Hubaga spring by this three-kilometer-long system. The aqueducts and springs in the area likely supplied the town’s old civilisation with the water it needed for drinking and farming. It is believed that the Romans constructed the aqueducts, although they remained in operation into the twentieth century. Archaeologist Ahmed Fakhry suggests that the aqueducts predate the Romans and may even date back to the time of Dynasty XXVI.

Bannentiu, the son of Djedamun-ef-ankh, was buried in the second tomb. He was a very successful and rich businessman. The size and ornamentation of his tomb exceeded that of his father’s. There were three separate rooms off to the side of the main hall, and their pillars were square. The tomb has recently been repaired by the Supreme Council of Antiquities, who painted it in a range of vivid colours, including red and earth tones.

The entrance to the tomb is protected by Thoth and Horus. Plastered images of the deceased stand before a leopard-skinned priest. His retinue of deities includes Horus, Amun-Re, Wepwawet, Anubis, Khons, Nefertum Re-Horakhty, and others. The Romans also interred their dead in these graves. In the twentieth century, criminals entered into the tomb of Bannentiu and stole a few reliefs, causing damage to the tomb’s decorations. In the end, the police were able to track down the perpetrators and retrieve the stolen bricks. The Cairo Museum is a safe haven for the reliefs. There has been no start to restoration activities as of yet.

The Decorated Tombs

The homes in Ain El-Hubaga include a number of obvious ventilation shafts. Fakhry continued his excavations close to the north of here in 1938, when he found four beautifully adorned and well-preserved tombs from the reign of the Dynasty XXVI.

Others believe that the rich landowner Djedamun-ef-ankh possessed two graves. His mausoleum is enormous, with circular pillars, painted religious themes, and phoney doors all over the place. Scenes depict Djedamun-ef-ankh presenting his tomb to the gods. Goddes Nekhbet is shown in several of the ceiling murals. The tombs are located at the bottom of a very deep hole, and the only way to get there is by way of an iron ladder.

Valley of the Golden Mummies

The Breakthrough Aharia has blossomed into a global landmark during the last several decades. Bahariya’s prominence rose once the location’s Roman necropolis was uncovered. The Valley of the Golden Mummies got its name from all the gilded tombs that can be seen there. In 1999, the public was made aware of this finding for the very first time. This occurred three years after antiquities inspector Ashry Shaker first notified Dr. Zahi Hawass of the mummies’ discovery. Scholars in the field of archaeology put the age of this golden cemetery at about the year 2000. The find was made when a guard riding a donkey in search of artefacts stumbled into a chasm on the side of the road. A town called Bawiti was around 6 kilometres away.

As a result of their preliminary research, they found 108 mummies spread over four graves. The first tomb to be uncovered revealed glittering gold, which had not been exposed to sunshine in generations. Dr. Hawass estimates that there are more than 10,000 mummies in the graveyard.

Graves of Roman Bahariya family. In each of the several rooms, there were many tiers of seats. Curiously, the graves were found in their original form, suggesting that they were never targeted by grave thieves. The mummies were discovered in elaborately decorated and gilded tombs. Some mummies were embellished with jewellery and had gilded face masks. Coins, wine jars, amulets, and ceramics were only some of the many artefacts found in and around the mummies’ graves.

There were four distinct mummification techniques used to uncover the necropolis’s mummies. The first fashion was seen on the mummies that were unearthed with gold deity-inspired ornaments on their chests and gilded masks on their faces. Second, there were colourfully decorated cartonnage coffins. The third kind had mummies being buried in plain, anthropoid-shaped clay urns. Cloth-wrapped mummies, typical of New Kingdom graves, constituted the last type.

The tombs are remarkable due to the high volume of human remains they contain. There were families represented by men, women, and their children, as shown by the proximity of some of the remains. The architecture of each tomb was likewise unique. Each mummy was uniquely embellished from the others. The tombs have a varying number of chambers. There was a wide range in the size of the rooms.

Some of the first excavations looked like the catacombs of Kom el-Shugafa in Alexandria, which were used by the Greeks and Romans. The walls of a second tomb that had been unearthed included niches. These actions were performed in advance of funerals. Neither grave was embellished with any kind of decoration.

There are still opportunities to enjoy the hot springs and stroll into the white desert to witness some stunning landscapes. To put it simply, Bahariya is the place to be if you’re the exploratory kind.

Golden Mummies Museum

While Bahariya has 10,000 mummies, only ten are on show here because to space limitations. The painted faces show a departure from stylised Pharaonic mummy adornment and a move towards Fayoum portraiture, even if the themes are repetitive and the craftsmanship is substandard. These mummies herald the end of mummification since the embalmers’ work seems shoddy underneath the wrappings. The exhibit is representative of that mindset; it’s boring and lacklustre. Unfortunately, the museum lacks any kind of directional signs. Under the shadow of a low, cream-colored wall topped with guard towers, you’ll find a structure that appears like it was plucked straight out of a military bunker.

The Temple of Ain Al Muftella

has four chapels built during the 26th dynasty and is situated two kilometres northwest of Bawiti. The grave of 26th dynasty high priest Zed-Khonsu-ef-ankh was unearthed in a crypt at Bawiti and is presently off-limits to the public. Researchers have concluded that the chapels’ origins date back to the New Kingdom, that they were greatly enlarged during the Late Period, and that they were enlarged once again during the Greek and Roman eras. All of them have been repaired and given new wooden roofs to protect them from the weather.

Tomb of Zed Amun Ef Ankh

Zed Amun Ef Ankh’s rock-cut tomb is an interesting look back to ancient Bahariya. Zed Amun Ef Ankh was not a government official, yet his tomb was decorated lavishly with vivid murals that suggested power and riches. His profession, according to the investigators, was trading.

Oasis Heritage Museum

Mahmoud Eid’s Oasis Heritage Museum is located 3 kilometres east of town on the road to Cairo. Its creator, inspired by Badr’s Museum in Farafra, captures scenes from traditional village life in clay, including men hunting and women weaving. There is also a display of old Oasis dresses and jewellery.

Ain Gomma

Located 45 kilometres south of Bawiti, this spring is often considered to be among the region’s most picturesque. This little pool in the middle of the desert is filled with cool, clean water from a nearby spring, and it’s next to the hippest café in the oasis. It’s in close proximity to Al Hayz.

Bir Al Mattar

Bir Al Mattar, located 7 kilometres northeast of Bawiti, has a concrete pool fed by cold springs that fall into a bridge. Like with all of Bawiti’s springs, the mineral level is high enough to leave stains on fabric.

Bir Al Ramla

Sulphurous spring, 3 km north of town, is very hot (45°C) and suitable for soaking.

Qarat Al Hilwa

This ancient necropolis contains the 18th-dynasty Tomb of Amenhotep Huy. Overall, it’s a rather uninspiring site that will only appeal to the most ardent archaeology fans.

Qarat Qasr Salim

Among Bawiti’s dwellings is a tiny mound that was presumably built from garbage accumulated over many decades or perhaps centuries. Two rather intact tombs dating back to the 26th dynasty were used by the Romans as community burial grounds. These properties include brilliant wall murals that have been painstakingly conserved. Zed Amun Ef Ankh’s tomb was carved out of rock and has colourful murals that hint to the past occupant’s riches, providing a look into ancient Bahariya at the city’s heyday. Bannentiu, son of Zed Amun Ef Ankh, was buried not far away. Fine reliefs depicting Bannentiu with the deity Khons and the goddesses Isis and Nephthys decorate the walls of the four-columned burial chamber and inner shrine.

El Jaffara

Located approximately 7 kilometres south of Bawiti, on the Bahariya-Cairo route, is the mini-oasis of El Jaffara, which is known for its hot and cold springs and is thus visited throughout the year.

Al Hayz Water Education Center

The little oasis of Al Hayz may be found between Farafra and Bahariya, close to the Ain Gomma.

The Water Museum is a must-see, since it gives a comprehensive picture of Egypt’s water resources and challenges, the geology of the Western Desert, the traditional agriculture and architecture of the oasis, and the measures that must be taken to alleviate water shortages. The museum itself is a beautiful structure; it was constructed using sustainable materials like basalt and rammed earth.

Black Desert

Once the sands turn from beige to black 50 kilometres south of Bawiti, you have reached the beginning of the Black Desert. Erosion from the mountains has coated the peaks and plateaus in a coating of black powder and stones, creating a panorama that seems like something out of Hell. Tours leaving from Bahariya Oasis often include a stop in the Black Desert as part of a larger itinerary that also includes the White Desert. The region also has the pyramid-shaped peak Gebel Gala Siwa, which served as a watchtower for caravans travelling from Siwa, and the mountain Gebel Az Zuqaq, which is notable for the red, yellow, and orange streaks in its limestone foundation.There is a well-worn trail that leads to the peak of the mountain.

Walking to the far east, where the wildest wonderland of white hoodoos may be found, would be a lengthy voyage. The water level in Bir Regwa, a small spring located close to one of the park’s entrances, is often rather high.

Ghard Abu Muharrik And The Sand Volcano

The Ghard Abu Muharrik is often visited on safaris that go to El-Qaf and stretch 20 kilometres to the east (“Dune with an Engine”).

Somewhere in these wastes, a guide from Western Desert Safari in Bahariya has uncovered a “Sand Volcano,” where sand seemingly erupts from the ground through a crack in the earth.

Crystal Mountain

As you make your way into the Farafra depression from Bahariya Oasis, you’ll be treated to a series of breathtaking panoramas. Here, safaris pull over so that visitors may gawk at Crystal Mountain (Jebel al-Izaz), a shining quartz ridge with a human-high natural arch across the centre.

Agabat, often known as “Wonders,” is the breathtakingly difficult landscape that can be found beyond Twin Peaks. The location is known as Akabat by some residents because of the loose sand and powdered chalk that can easily trap automobiles despite the area’s visual feast of pale rock “sugar loaf” (“difficult”).

White Desert National Park

“The sun goes down over Egypt’s White Desert, which is part of the Western Sahara Desert.” The White Desert of Egypt is 45 km (28 miles) north of Farafra. “The desert is white and cream-colored, and it has huge chalk rock formations that were made by sandstorms in the area,” says Wikipedia. When you first see the White Desert’s 300-square-kilometer national park, you’ll feel like Alice in “Through the Looking Glass.” About 20 km northeast of Farafra, on the east side of the road, blinding-white chalk rock spires seem to grow out of the ground almost magically. Each frost-colored lollipop has been licked by the dry desert winds into a surreal landscape of familiar and strange shapes.

The best times to see these sculptural formations are at sunrise or sunset, when the orange-pink light of the sun shines on them, or at full moon, when the landscape looks like it belongs in the Arctic. The sand around it is full of quartz, small fossils, and different kinds of deep-black iron pyrites. Chalk towers called “inselbergs” rise from the desert floor into a beautiful white canyon on the west side of the Farafra-Bahariya highway, away from the wind-carved sculptures. They are linked by grand sand boulevards that look like the geologic Champs-Élysées. This is a great place to camp because it is shady and private, and it is just as beautiful as the east side of the road.

The Twin Peaks, which are two flat-topped mountains about 50 km to the north, are an important landmark for travelers. The view from the top of the symmetrical hills around it, which all look like giant ant hills, is amazing, which is why local tour companies love to take people there. Just past here, the road goes up a steep cliff called Naqb As Sillim, which means “Pass of the Stairs.” This is the main pass that goes into and out of the Farafra depression and marks the end of the White Desert.

A few kilometres later, the desert floor changes again. There are now quartz crystals all over the ground. When you look at the rock formations in this area, you’ll notice that most of them are made of crystal. The most well-known formation is Crystal Mountain, which is a big rock made up of only quartz. It is about 24 km north of Naqb As Sillim and right off the main road. The big hole in the middle makes it easy to find.